LPRFacts

State and federal lawmakers have increasingly moved to target a powerful technology used by law enforcement to solve crimes and save lives.

State and federal lawmakers have increasingly moved to target a powerful technology used by law enforcement to solve crimes and save lives.

NetChoice has released a white paper for law makers exploring the basis for these legislative attacks, and separating fact from fiction as it relates to automatic license plate recognition (ALPR) technology.

The paper identifies a strong legislative structure already in place to protect consumers and highlights the negative impact of lawmakers targeting specific technology, rather than technology-neutral behavior.

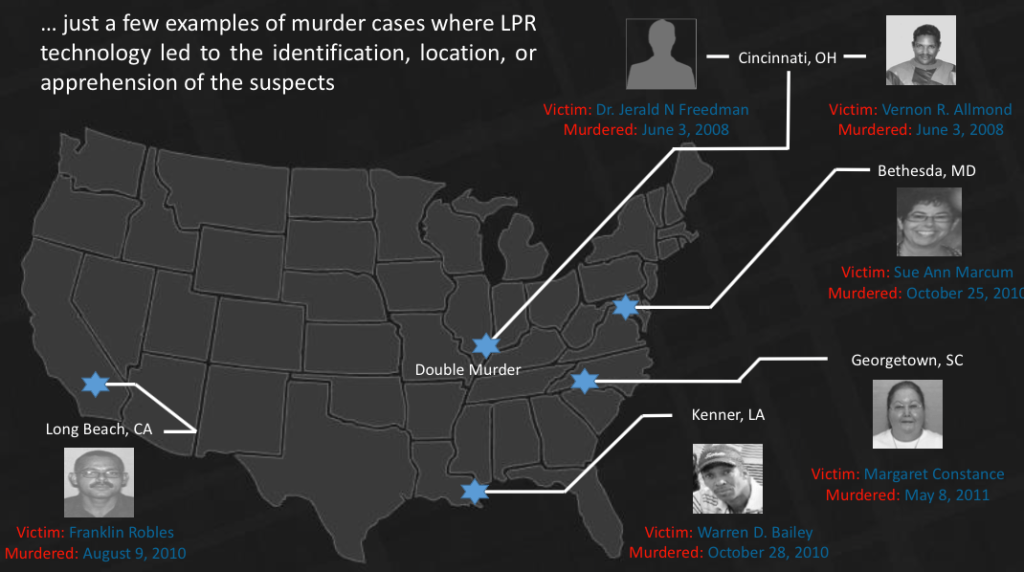

LPR helps save lives and solve crimes

Law enforcers are fighting to preserve LPR technology for one reason: it works. Both anecdotal accounts and comprehensive data analysis reveal a technology that has solved crimes and protected victims.

- In the first 30 days of having access to a national LPR data network, the Sheriff’s Department of Sacramento County located 495 stolen vehicles, 5 carjacked vehicles, and 19 other felony vehicles (45 people were arrested).

- A 15 year-old girl was abducted in New York and taken to Maryland. LPR data led to the rescue of the victim.

- A mother reported her daughter missing after being unable to reach her for over a week. Detectives used LPR data to locate the daughter’s vehicle on three occasions in the same apartment complex in the prior week. Working with property management, the detectives located the daughter, who was close to death.

- Police used an LPR database to locate a fugitive responsible for identify theft crimes against ailing and deceased veterans. Around 50 victims reported charges on their credits cards entered with their names. All were from the same Veterans Affairs hospital in California. A suspect, who was an employee of the VA facility fled to the Chicago area. Using the services of an LPR provider, the police located the fugitive’s vehicle in the Chicago area and she was arrested and pled guilty to the identify theft charges.

Privacy already protected under existing law

Technology-specific legislation is not needed for LPR, in large part because LPR data and its use is already covered under strong federal privacy law that focuses on behavior, rather than technology.

Drivers Privacy Protection Act:

The federal DPPA was enacted in 1994 and its purpose, as stated in the bill’s preamble, was: “to protect the personal privacy and safety of licensed drivers consistent with the legitimate needs of business and government.”

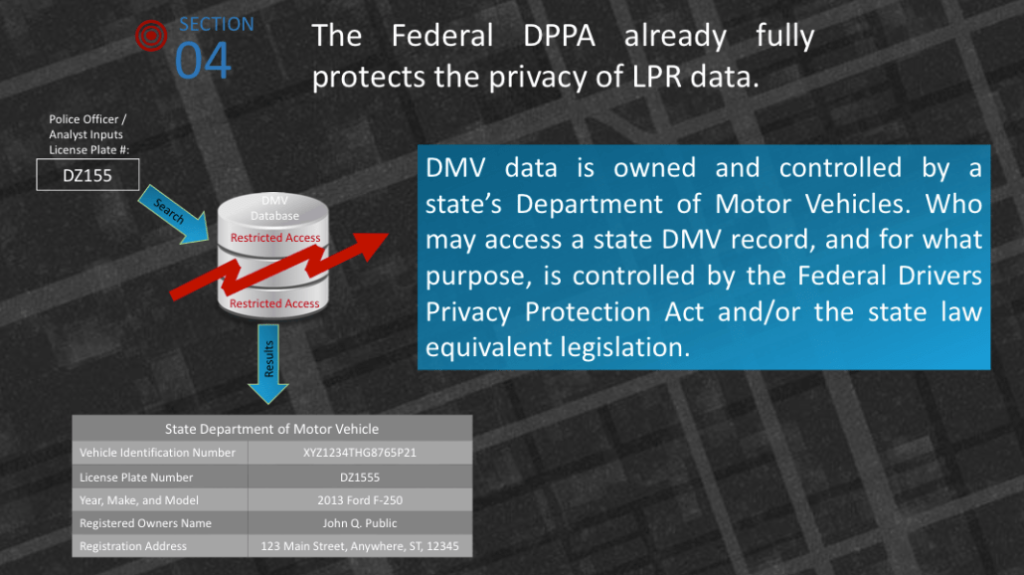

Congress enacted the federal Drivers’ Privacy Protection Act of 1994[1] to provide strong privacy protections regarding personally identifiable information held by state DMVs. The DPPA’s purpose, as stated in the bill’s preamble, was “to protect the personal privacy and safety of licensed drivers consistent with the legitimate needs of business and government.” More recently, the U.S. Supreme Court summarized the legislative history and explained that Congress decided to override state laws with the DPPA because of “the States’ common practice of selling personal information to businesses engaged in direct marketing and solicitation.” Maracich v. Spears, 570 U.S. (June 17, 2013).

To protect privacy, the DPPA made “unlawful” any use of personal information obtained from motor vehicle offices (e.g., data taken from car registration or drivers’ license applications) without consent unless it is for specific purposes authorized by the law such as for law enforcement; for any “private person or entity acting on behalf of a Federal, State, or local agency in carrying out its functions;” and for the execution of service of process or enforcement of judgments and orders pursuant to court orders; and for other purposes. (See, 18 U.S.C. 2721 – 2725).

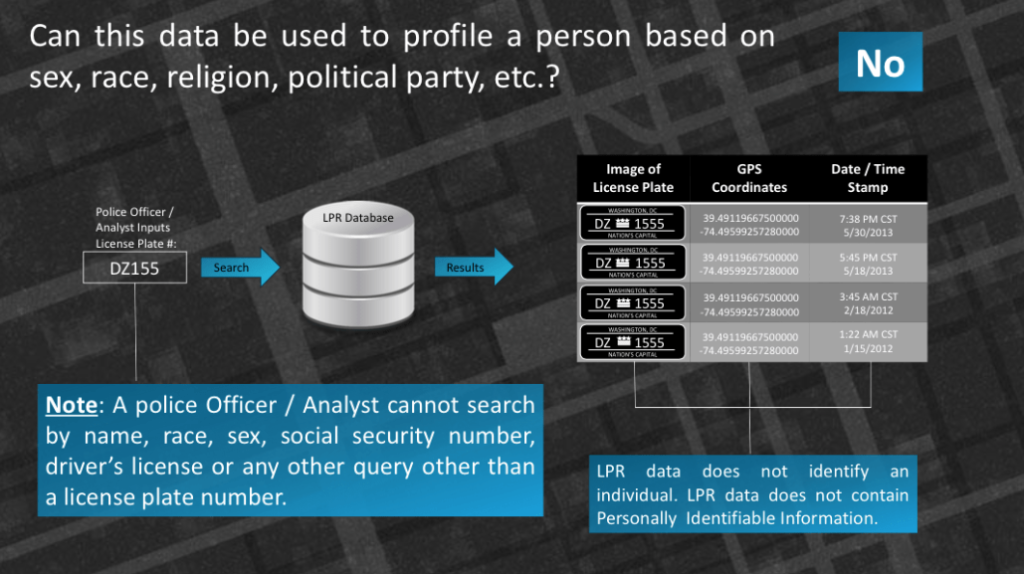

Because of the protections put in place by the DPPA, the inability to connect license plate numbers to protected personal information held at DMVs without an expressed permissible purpose means that license plate numbers (whether obtained by writing them down, or by taking pictures manually or automatically with ALPR cameras) are anonymous data.[2]

Note that the DPPA applies to any person – not just law enforcement – who misuses personal information and the DPPA applies to any person who makes a false representation to obtain any personal information from an individual’s motor vehicle records. It is a very tough law in that actual harm (damages) does not need to be proven to get a judgment against persons who violate that law. Kehoe v. Fidelity Federal Bank & Trust, 421 F. 3d 1209 (11th Cir. 2005), cert. denied.

DPPA provides for criminal fines for substantial noncompliance by State DMVs of not more than $5,000.00 per day of such noncompliance. Persons found in noncompliance are subject to civil action in U.S. district courts and may be ordered to pay actual damages, but not less than $2,500 in liquidated damages, reasonable attorneys’ fees and litigation costs, and punitive damages, if justified.

As long as strong data privacy protections are in place, there should be no restriction on the ability of our protectors to take advantage of technology that helps them protect us. Privacy safeguards can be strengthened at the federal level with minor changes to the DPPA. At the state level, current DPPA provisions protecting the privacy of personal data held at the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles are sound. Measures recommended by some privacy advocates – including arbitrary time limits on how long anonymous ALPR data[3] can be stored – would clearly impair law enforcement’s ability to identify and rule out or exonerate criminal suspects, rescue victims, capture fugitives, prevent terrorist attacks, or arrest persons actively involved in crimes.

[1] The federal DPPA law was introduced in the Senate (S. 1589) in 1993 by Senator Barbara Boxer (with Senators Dianne Feinstein, Barbara Mikulski, Patty Murray, Tom Harkin and several other Senators). The House companion bill (H.R. 3365) was introduced by Congressman James Moran (with many cosponsors). President Clinton signed the bill as passed by the Congress.

[2] A few people pay extra for a “vanity plate” which could include their name.

[3] The use of historical data is very important regarding fighting organized crime and making longer-term associations regarding criminal gangs, drug trafficking organizations, and similar larger crime networks. In California, bank robbers took over a Wells Fargo bank but a witness got a license plate number as the suspects fled. A check of ALPR data showed the vehicle on a major highway six months earlier. Officers canvassed the area and quickly found the vehicle. They did a stake out and made the arrests.

In addition to existing legal protections, ALPR technology and data companies voluntarily impose strict requirements and limitations on the use of their data, and routinely monitor database access to prevent misuse or abuse. The combination of strong legal protections and industry’s self-imposed data restrictions is why there has been no demonstrated pattern of ALPR data abuse anywhere in America.

The ACLU report incorrectly notes that ALPR is being “used to record Americans’ movements” and thus “trace a person’s past movements.” There are two things wrong with this characterization. First, ALPR technology does not know who is driving or who is in the car. Second, it does not continuously trace all movements – it is not a continuous surveillance tool like GPS technology. ALPR techology only takes “snapshots” of a license plate (and the attached car) and notes the location, time, and date if a plate happens to be within view of a camera

This is very different from GPS tracking technology, which is capable of tracing all of a vehicle’s movements over time with high precision and involves physical trespass upon private property (a vehicle) in order to place a tracker. Because of these unique features of GPS technology, the Supreme Court in its 2012 Jones decision determined that GPS tracking constitutes a “search” under the Fourth Amendment and should be subject to a warrant requirement.

The ACLU report also expressed concern that license plate numbers can be used by the police “to identify protest attendees merely because these individuals have exercised their First Amendment-protected right to free speech.” The ACLU offered a helpful solution. They suggest that “only agents who have been trained in the departments’ policies governing such databases should be permitted access, and departments should log access records pertaining to the databases.” Fortunately, those practices are already in place thanks to requirements under the federal DPPA, requirements under individual agency policies, and strict requirements voluntarily imposed in contractual data use agreements between private ALPR data companies and their customers.

We also agree with the ACLU’s position that taking photographs of things in plain view is a constitutionally protected activity. This includes license plates. As of August, 2013 the ACLU website notes that:

“When in public spaces where you are lawfully present you have the right to photograph anything that is in plain view. That includes pictures of federal buildings, transportation facilities, and police.”

This point is highlighted in ACLU legal briefs filed in court where they point out that the ACLU films and records audio of persons at demonstrations including the police because there is a “right to record information about the public activities of others.”

The ACLU concludes that there is a “specific right to record information about the public activities of others . . . [including] recording ‘street activities’.” and there is a right to broadcast those movies of citizens, including police, in public places. The ACLU could then, “where appropriate” broadcast the recordings through “evolving internet and electronic media” such as through “Facebook, Twitter, and the ACLU’s own ‘action alert’ email network’”[1] They cite many cases for the proposition that “[c]ourts in myriad contexts protect the right to gather information for subsequent public dissemination.” See e.g., Richmond Newspaper v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555 (1980). (Emphasis added.) In contrast, the DPPA makes unlawful any dissemination of personal data including the photos and addresses of persons applying for driver’s licenses except under very specific conditions.

[1] ACLU brief filed in ACLU v. Anita Alvarez, US Court of Appeals, 7th Cir; No. 11-1286 (Aug. 15, 2011), see especially pp. 12, 13 and 21.